“Ultimately it comes down to the desire to be where our customers are, to play fair with them in the assumption that they’ll play fair with us. And you know something? It’s worked.”

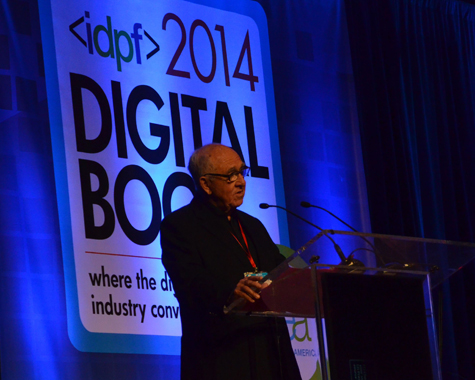

Tor Books president and publisher Tom Doherty had a lot to say during his speech at the International Digital Publishing Forum at this year’s 2014 Book Expo of America, but the main item on the agenda was Tor/Forge Books’ decision to strip Digital Rights Management software from the ebook versions of their titles and whether, two years later, that decision has had any negative impact.

In the case of Tor Books it appears that it hasn’t, but as Doherty pointed out in today’s speech, the implications of DRM go beyond the financial impact to publishers, authors, and readers. Insidiously, it chips away at the very connectivity that the entire publishing community has always relied upon.

Those invested in for-or-against arguments for DRM are most likely well-versed in how the software affects publishers and authors on a financial basis, as well as how it affects the sentiment of more techno-savvy readers. And while these arguments certainly played a role in Tor Books’ decision to forego DRM in its ebooks, Doherty spent a good portion of the speech discussing the community that these arguments exist within: a publishing community that consists of all levels of participant, from “bookseller, author, reader, and semi-pro.”

As it turned out, framing DRM within this larger context was quite intentional and key to understanding the motives behind the move. Publishing, Doherty argued, has always been a community of support and conversation, driven and refreshed by the excitement generated by the authors and their stories. During the speech, the publisher related a story about how the success of Robert Jordan’s The Wheel of Time was built on the excitement that every aspect of that publishing community brought forth:

“…like any #1 fan, I just wanted the whole world to know about this story, this world [Jordan] was creating. From page one of Jordan’s first Wheel of Time book “The Eye of the World,” at about the length of a novella, there was a natural breakpoint. To that point there was a satisfying story that really involved me. There was no way I was going to stop there and I didn’t think others would either. So we printed I think it was 900,000, long novella-length samplers, and gave them to booksellers in 100-copy floor displays to be given free to their customers. We gave them to fans with extras to give to friends, to semi-pros, and readers at conventions and anyone in the publishing community who we thought would feel the excitement that we felt. […] We’re a community of many people, many of them here to talk about the stories that we find to be terrific.”

And from there you get #1 New York Times bestselling writers like Brandon Sanderson, notably inspired by The Wheel of Time. You get communities like Tor.com, where readers have been talking non-stop about the fiction that excites them. You get authors like Jo Walton finding new fans by engaging in a substantive manner with those communities. Although we now have digital spaces to house this kind of interaction, it has always been taking place in the physical spaces of the science fiction/fantasy publishing community, Doherty argued. It is, in fact, “a connection they make naturally. Barriers, whether it’s DRM or something else, disrupt these natural connections.”

In this context, the implications of DRM came off as a regressive step, especially when, as Doherty was quick to point out, Tor Books’ competition in the marketplace had already discarded DRM as regressive without suffering any ill effects:

“Baen, which was a real pioneer in e-book publishing, has always been DRM-free. The language that Baen’s fans use in praising this, and in complaining about the rest of the industry, can be…bracing! And also passionate and articulate. And of course Baen is a major competitor in science fiction and fantasy. We certainly want the Tor customer to feel good about us, too.”

And from a marketplace perspective, it appears that Tor Books has achieved the same results. In a decisive statement, Doherty declared:

“…the lack of DRM in Tor ebooks has not increased the amount of Tor books available online illegally, nor has it visibly hurt sales.”

Although it seems like such a statement would put a button on the issue, there was more to consider in regards to keeping the interactivity of the community healthy and vibrant. More than supporting the existing stories and the formats they reside within, having a DRM-free digital space for the sci-fi/fantasy community also allows for experimentation with format, such as the TV-season-esque serialization of The Human Division, the latest novel in John Scalzi’s Old Man’s War universe.

And the new Tor.com ebook imprint!

This new imprint, separate from Tor.com’s current short fiction publishing program, will be publishing original DRM-free ebook novellas by authors both known and unknown. Why novellas? Doherty explained.

“…we see it as a way for science fiction and fantasy to sort of reclaim the length of the novella, a format that I have always felt is a natural form to science fiction. A format that was very important when magazines were dominant in SF readership but which has almost disappeared as that market declined. A format we used in building Robert Jordan into the #1 epic fantasy novelist of his day. Readers have a wide range of reading appetites in regards to the length of a story, a range that a book publisher and a printing press can’t necessarily always react to economically.”

The announcement came as a bit of a surprise (you can find the official press release about it here if you want more info) and Doherty couched the development of the Tor.com Imprint as parallel to going DRM-free. The Tor.com Imprint will develop a format and delivery system that has already become a natural part of how readers find new stories. You can keep a reader or a bookseller or an author or a semi-pro excited about a story by publishing an easily accessible novella in between novels, you can more easily build a more diverse publishing program, and you can do it without locking those stories into devices that may or may not become obsolete. The imprint, going DRM-free, these are both ways to keep our publishing community excited.

And you need that when your stories exist on the frontiers of thought. “We’re all out here together,” Doherty said. “And you can’t put up barriers or turn a deaf ear to the community that keeps you exploring.”